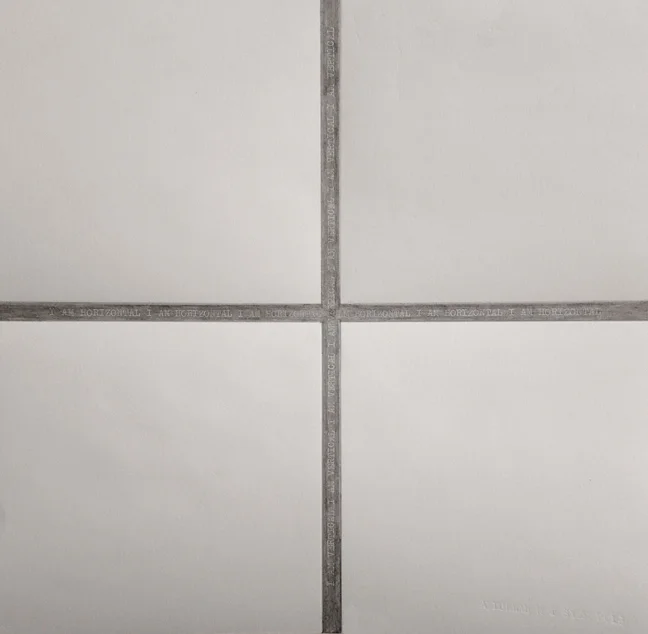

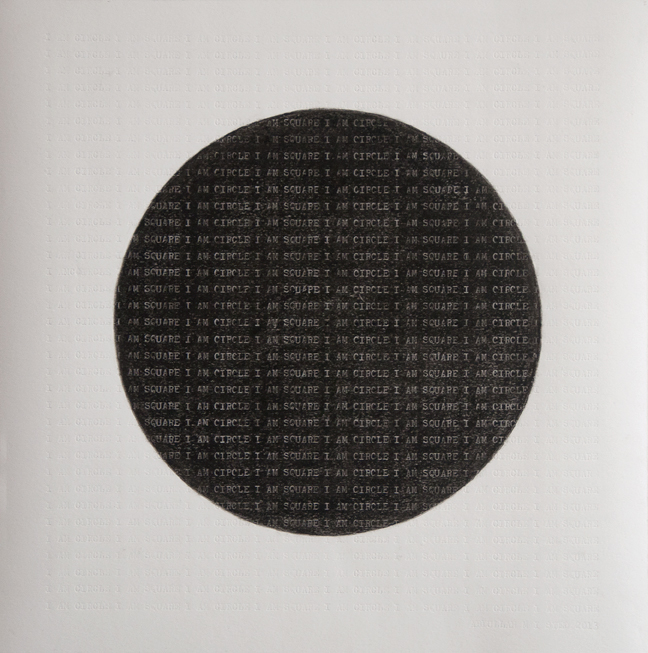

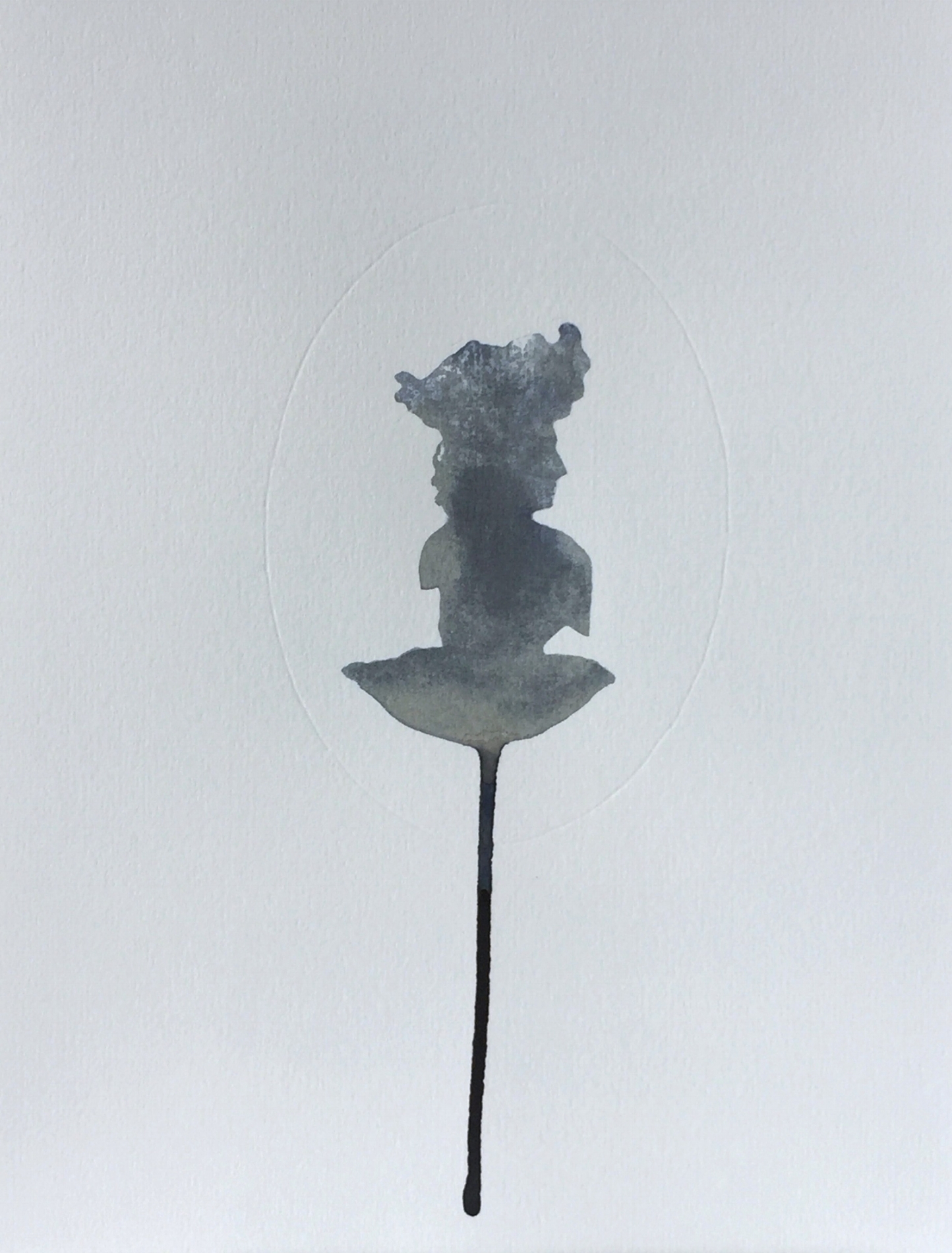

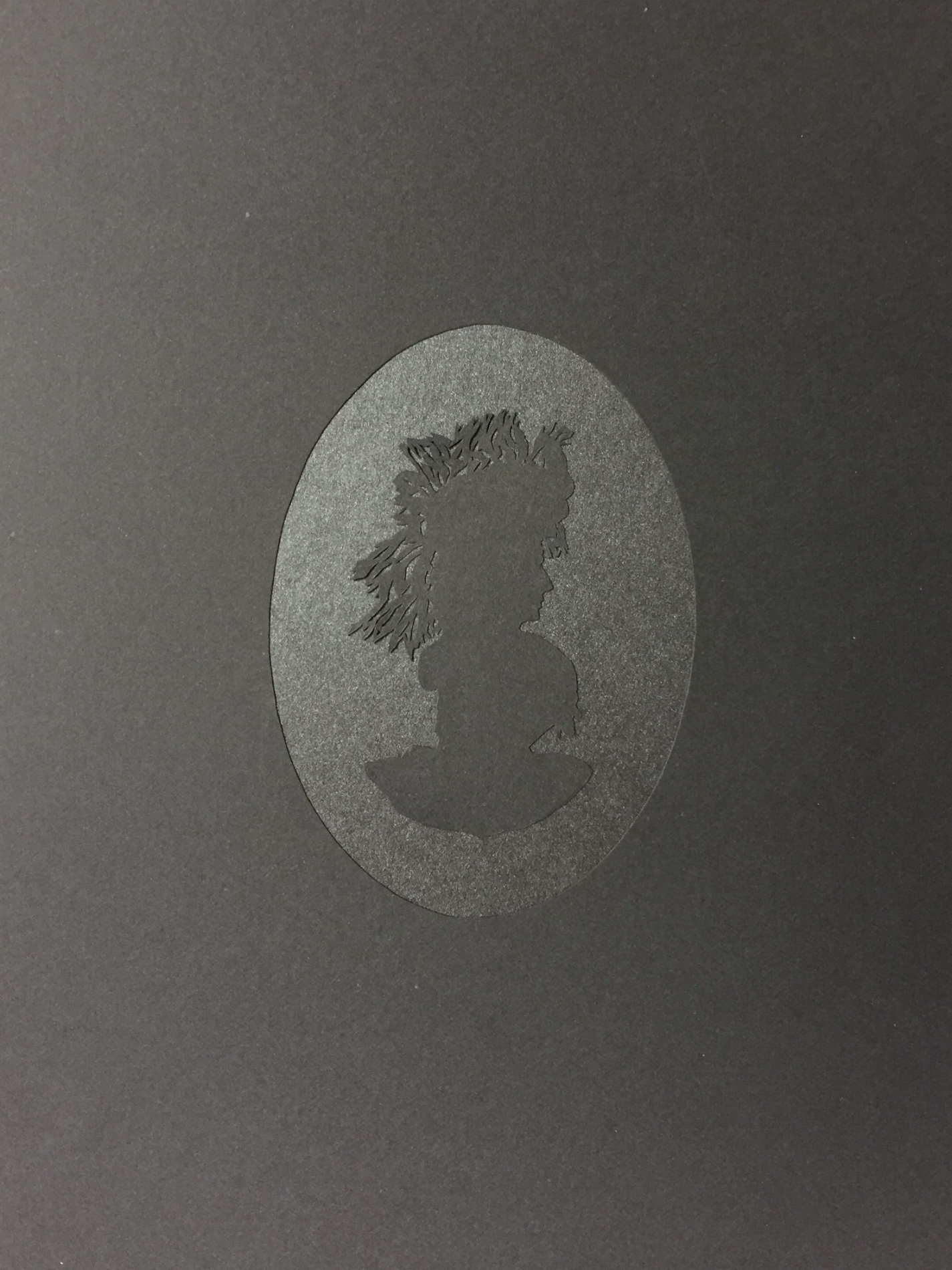

Appearing across currency, stamps, history books or hanging in offices and museums, portraits of governing officials and their families not only communicate and mythologize their power in the state but are also intended to echo their legacy. For Governance, the lack of archival presence of the unassuming but heavily utilized and loved silhouette portrait of Lady Mary Rose FitzRoy (wife of Sir Charles Augustus FitzRoy the tenth Governor of the colony of New South Wales) - who inhabited the Old Government House Parramatta - was highly intriguing. The portrait’s provenance does not identify the artist and year of execution; neither does it demonstrate itself to be an intended communication of Lady FitzRoy’s achievements in the community, or the qualities she possessed. Yet the messy ink marks and crude execution of the silhouette hauntingly mirror the very tragic and gruesome death of Lady FitzRoy - the only thing about her that was recorded in detail. The cause of her death, a tragic horse carriage accident, even formed most of her obituary, overshadowing what little was known about her aristocratic roots, her “good looks”, “dignified, unaffected manners” and “amiable disposition which formed a large circle of friends.”

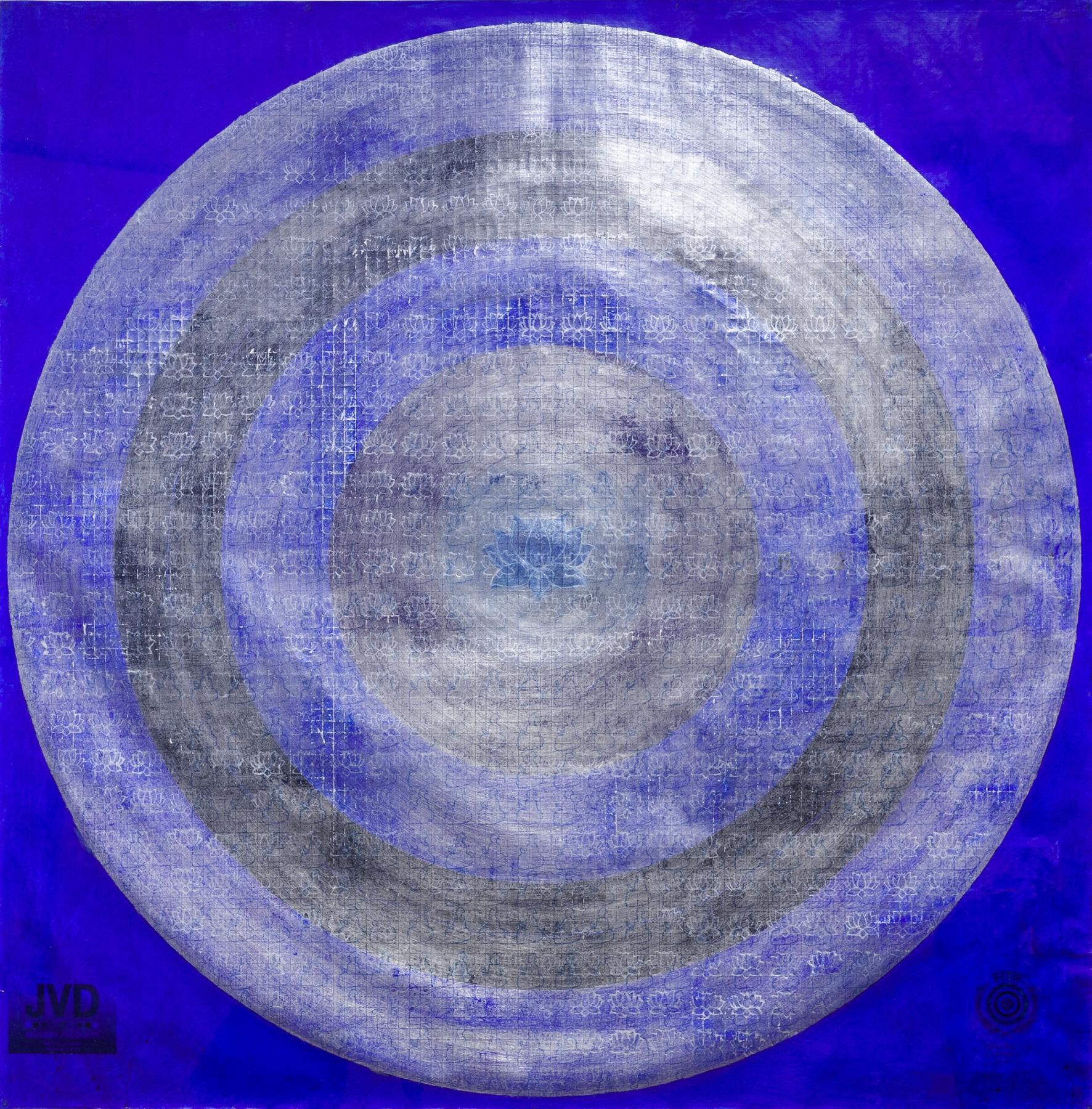

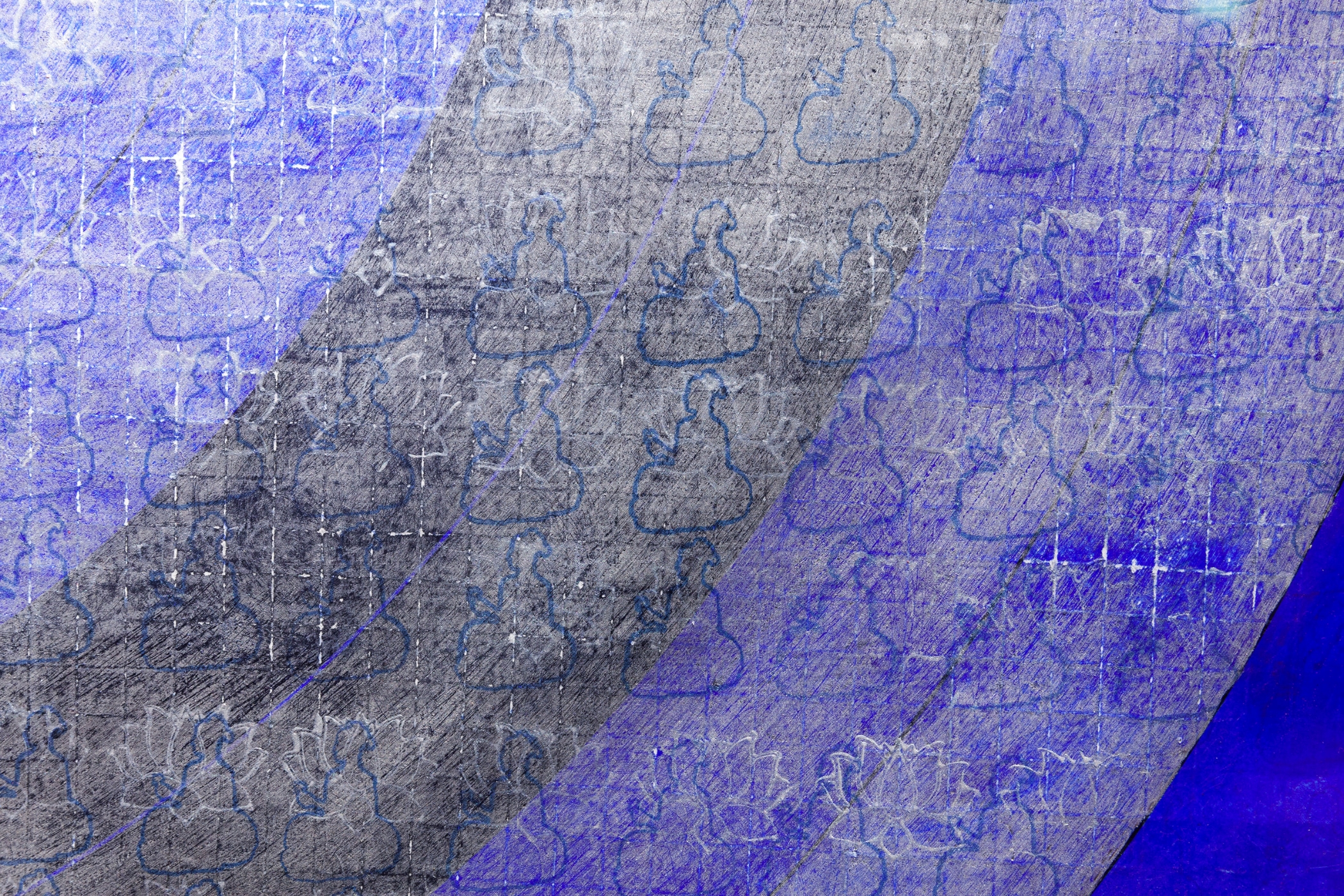

Myth of a silhouette and Bust takes such omissions and aesthetic erasures as a point of departure to relationally speculate the recorded history, creating realms of conceptualization where alternative visuals spin expanded narratives. She was a migrant, an industrious community worker, animal lover, avid gardener, passionate homemaker, lover of arts and craft and most importantly a much-loved public figure. Collectively, the works draw a new picture of Lady FitzRoy and how her life matters today.

Governance Exhibition, Old Government House, Parramatta